Oaxaca ~ Part IV

The Villafrontu District lies in the northern hills overlooking Oaxaca. It is a neighborhood of gracious Quintas, large estates enclosed within high adobe walls. These compounds generally contain a great house on expansive grounds with other smaller dwellings and well tended gardens.

For five generations the Olguin family had lived within the Quinta on their estate. The grounds within the walls covered one hectare (2.5 acres). In traditional Hispanic culture the oldest son inherited the property. Guillermo Olguin, now in his sixties was the current patriarch of the estate. He and his wife Ramona shared the main house with their eldest daughter Luciana. Two other children, son Diego and daughter Carmen both lived abroad. There were three other casitas within the terraced, hillside compound. Each was unique in design and construction, reflecting the different eras when they were built. Mature trees of many species were everywhere on the grounds.

The Olguins leased the casitas to writers, archeologists and others who came to Oaxaca for extended stays. Luciana’s old friend, Diane Sloane, now occupied one of these dwellings.

Diane did not come to Oaxaca to learn Spanish. She came to spend time with her old friend, Luciana Olguin. Many years before ‘Lucy’ and Diane were roommates at Northwestern University. For three years they were like family to each other. Then Lucy was involved in a car crash that left her paralyzed from the waist down.

Reluctantly, Lucy returned to her home in Mexico for rehabilitation and the care of her family. Over the years that followed, Diane and Lucy stayed in touch with written correspondence and occasional phone calls.

After college, Diane lived in Europe for a few years where she took up photography. In time she became a photojournalist. Her coverage of events like the Oktoberfest in Munich and the running of the bulls in Pamplona won her journalism awards and brought other assignments.

In the early ’90s Diane went to Alaska for a photo spread on the fisheries of the Cook Inlet. She was drawn to the people she met there. Qualities of character, the stories they told and their day-to- day enthusiasms presented a culture that Diane had never known. The vast wildness of the land also captured her imagination. She knew she was seeing the last vestiges of the American Frontier and wanted to be part of it.

At the south end of the Kenai Peninsula Diane rented a cabin near the fishing port of Homer. There she began her adventurous life in Alaska. Learning to fly she found work as a bush pilot. One morning at a cafe in Homer she she struck up a conversation with Paul Girard, a veteran fishing boat captain. He was surprised to learn that Diane lived near Homer. Paul liked her mettle and told her he needed one more deckhand for his next offshore voyage. He asked her if she’d like to ‘go fishing‘.

“I won’t kid ya,” Paul said, “the work’s hard and it can be dangerous. But the money’s good and you will experience life at the top.”

Once aboard Girard’s vessel ‘Lollypop’ Diane took to the sea like an old salt, quickly learning the ropes and holding her own with the seasoned deckhands. As other voyages followed, she became one of the few women who worked the fishing boats in Alaska.

In the summer of 1995 Diane met Phillip Sloane, a celebrated Alaskan bush pilot. The two began a stormy love affair, which led to a stormy marriage. Phillip had a weakness for whiskey and native women. Diane had a weakness for Phillip. She continued to work on the fishing boats, and would be out at sea for weeks at a time. Passionate reunions then painful disagreements would sometimes lead to brief separations.

On a Sunday morning in the spring of 2000, Phillip was flying medical supplies out of Anchorage to Native villages in the Interior. Sudden inclement weather caused his plane to crash in a remote area of the Denali Wilderness. During the search for the wreckage Diane flew one of the spotter planes. Eight days passed before the crash sight was found. An autopsy determined that Phillip had survived the crash but was killed by a Grizzly Bear.

When Lucy learned of Diane’s loss, she invited her to come for a stay in Oaxaca. Late in the following winter Diane decided to leave Alaska to spend time in Mexico with her old friend.

It was early in the evening when Diane walked up the path to the main house to share dinner with the Olguins. She brought with her a bottle of wine she had purchased during her day in the City.

Lucy was waiting for Diane when she arrived at the front patio. “Buenos noches amiga”, Lucy said.

“Hola mi amor”, Diane replied, as she sat down on a chair across from Lucy.

“How was your day?” Lucy asked.

“I was a tourist today,” said Diane. “Museums, Cathedrals, and the like.”

“Meet anybody interesting?” Lucy inquired.

“No,” Diane said. “Well, there was a brief encounter with another American.”

“Tell me,” Lucy said.

“Not much to tell,” Diane said. “He joined me this morning at my table on the Plaza.”

“He?” Lucy said. “And?”

“It was nothing really,” Diane said. “He only spent a few minutes there and then he left.”

“Por qué… Why’d he leave?” Lucy said.

“I asked him to,” Diane said.

“You asked him to leave,” Lucy said. There was a pause in the conversation.

“There was something about him,” Diane said, “I’m not sure. He seemed troubled. I don’t know.”

“Why would you ask him to leave?” Lucy said.

“I wanted some privacy.”

“Diane.” Lucy said, “At the Zocalo?””

“It’s funny,” said Diane, “there’s nothing like a crowded place in a strange city to make me feel…. alone. Invisible.”

“Invisible?” said Lucy.

“Kind of dreamlike, with a sense of mystery and empowerment,” said Diane.

“Well?” Lucy said, “… okay.”

“He was an older man,” Diane said.

“Who?” Lucy said.

“Ben,” Diane said. “The man at the Plaza.”

“So then, this was a five minute love affair,” said Lucy.

“A what?” said Diane.

“You know,” said Lucy, “those little encounters we have, like when you’re waiting in line at a grocery store. You’re next to a total stranger and suddenly you open up to each other. There’s just the two of you. You’re having this moment. It’s intense and there’s a sense of abandon about it. And while it’s happening, it’s the all and everything. And then it’s over. One person checks out their goods and bids farewell to the other. It’s done. Finished. Gone forever. But while it was happening, there was just the two of you… and no one else.” Lucy took a deep breath and slowly exhaled. For a long moment, Diane was completely still.

“Yes,” said Diane.

“Sorry,” Lucy said, “I do ramble on.”

“I hope you write this stuff down,” said Diane.

“I know,” Lucy said. “Lets go in, time for dinner. Give me a push?”

Diane steered Lucy across the bumpy tiles of the patio and through the entryway into the house.

Earlier in the day, Guillermo and Ramona Olguin returned home from a month in Italy. They spent most of their time in Florence where their son Diego worked at the Mexican Consulate. Diane and Lucy entered the dining room just as Guillermo was pouring wine into two glasses.

“Mama, Papa,” said Lucy, “Do you remember Diane?”

“Of course we do,” said Guillermo.

“Dearest Diane,” said Ramona, “It’s been a long time.”

“Señor y Señora Olguin,” said Diane, “Estoy tan feliz de verte.”

“Diane… please,” said Guillermo. “Let’s speak English tonight. Ramona and I need the practice.”

“Yes,” said Ramona. “We’re going to Seattle next week to see my family and none of them speak Spanish.”

“That’s fine by me.” Diane set the bottle of wine she was carrying on the table. “This is for you.”

Guillermo picked up the bottle and smiled. “Oh…”Dos Buhos.’ I know this vineyard. You have good taste, Diane. Let’s save it for later.”

They all sat down at the table and Guillermo poured Diane and Lucy glasses of wine. “Well,” said Guillermo, “to old friends.”

“To old friends,” the others echoed.

Juana, the Olguin’s elderly cook, appeared at the table.

“Buena noches,” she said.

“Buena noches Juana,” they replied.

Looking at Diane, Juana said, “Good evening.”

“Good evening Juana,” Diane responded.

Looking over at Ramona, Juana asked, “Aperitivos?”

“Si, Juana,” said Ramona, “por favor.”

Juana left the room. For a few moments the four people were silent, while looking at each other with half smiles, then serious expressions.

“Let me say,” said Ramona, “how very sorry we were to hear of your loss.”

“Yes,” said Guillermo. “You have our deepest… simpatîas..“

“Sympathies,” said Ramona.

“Sympathies,” echoed Guillermo.

For a long moment, everyone was silent, their eyes casting about each other.

Then Diane said, “Thank you. It’s been now. I’m done with shock and denial. What I feel now is mostly anger and bargaining.” Diane closed her eyes, with raised eyebrows bowed and slightly shook her head.

“We’re all acquainted with grief,” said Guillermo. “You stay with us as long as you like.”

“Thank you Don Guillermo,” said Diane.

After another long moment of silence, Guillermo said, “The wine you brought, it comes from Dos Buhos Vineyards, in San Miguel de Allende.”

“I know San Miguel,” said Diane. “I was there with Phillip a few years ago.”

“When I was a boy,” said Guillermo, “I would visit my cousins there during the summertime.”

Diane nodded.

“In those days San Miguel was still Old Mexico,” said Guillermo. “My favorite memories are of summer evenings at the Plaza.”

“Oh Papa,” said Lucy, “… that story again?”

“Hiha… for Diane,” said Guillermo.

“Si Papa. Disculpeme.”

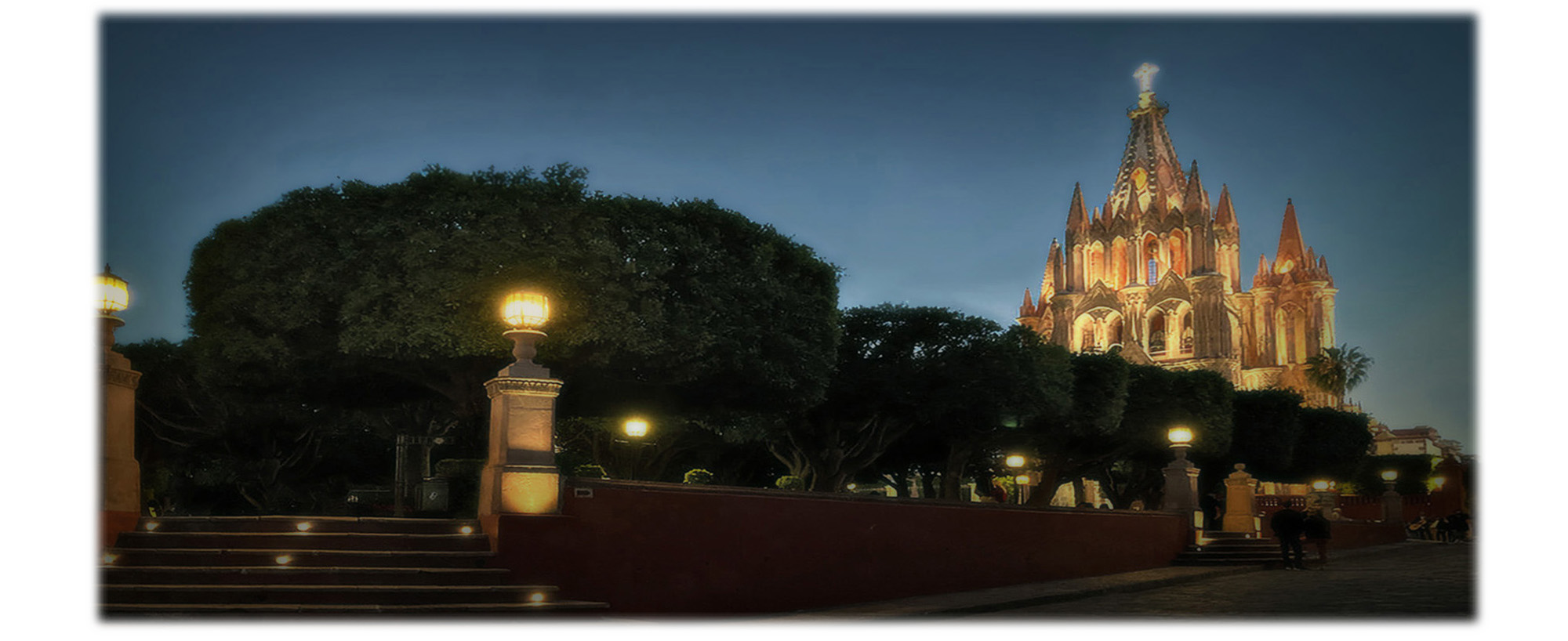

Guillermo smiled, glanced over at Ramona then looked towards Diane. “In San Miguel, the Plaza was called “El Jardîn”. It was framed by a broad, granite sidewalk which was wide enough for two people to walk side by side in one direction while passing two others who were coming the other way. The Jardîn itself was filled with tall Laurel trees and lush flower gardens. Walkways threading through the gardens were lined with ornate, wrought iron benches, and at the center was an elevated gazebo.

Diane smiled and nodded.

Guillermo continued. “The surrounding streetlights provided a warm ambiance, which illuminated the sidewalks and dappled through the trees into the Jardîn. Across the street on the south side was the commanding presence of the San Miguel Cathedral. At twilight boys and girls, mostly in their teens, would arrive in twos and threes, having walked there from their homes.”

“How many would there be, I mean in total?” asked Diane.

“On a busy night there would be at least a hundred,” said Guillermo.

“A real crowd,” said Diane.

“For good reason,” said Guillermo. “The young people joined together in a splendid procession. The boys would walk around the Jardîn on the outside of the sidewalk in a counter clockwise direction while the girls walked clockwise on the inside. They’d walk in pairs, the boys in one direction and the girls in the opposite direction. It always began at a quickstep, probably because everyone was nervous. As the evening progressed the pace would slow down to a stroll.”

“I get that,” said Diane.

“Yes,” said Guillermo. “They would walk in pairs, the boys going one way and the girls going the other way. As the evening unfolded, everyone walked at a slower and slower pace. Passing each other, the boys and the girls were constantly trading glances and looks and smiles.. and sometimes frowns.”

“Just out of curiosity,” said Diane, “how long did it take to go around the block?”

“All the way around the block,” said Guillermo, “was maybe two hundred meters. Initially, it would take two or three minutes. But after things slowed down, it took much longer.’

“And this went the whole evening?” said Diane.

“Two, sometimes three hours,” said Guillermo. “Everyone would pass each other twenty to thirty times in an evening. As the evening would unfold, eventually flirtations would arise. A boy and a girl would stop and step out of the traffic and talk to each other. Of course, they would each have their friend with them – friends who were “seconds”, witnesses to the encounters the interested parties were having. It was amusing to see how the friends related to each other in contrast to the romantic exchanges of the would-be, smitten pair. And after those initial encounters, the boys and girls would usually rejoin their ranks in the procession and continue on their quest.”

“Quest?” said Diane.

“To find a mate,” said Ramona.

“Yes,” said Guillermo. “Then, after another two or three more rounds of the Jardîn, the same boy and girl might stop again. This time their friends would continue in the procession. At this point, the couple might walk into the Jardîn and sit down on one of the ornate benches where they’d continue with their acquaintance. But they weren’t alone.”

Diane smiled.

“Throughout the evening,” said Guillermo, “there would be eight or ten abuelitas, grandmothers seated on various benches in the Jardîn.They would sit quietly, observing and lending a certain propriety to the occasion. Fifty years before, many of these women had engaged in the same rituals, which they now attended as chaperones. And some of these boys and girls were their nietos, their children’s children.”

Guillermo fell silent.

Juana the cook reappeared with apertivos and glasses of water. As she set the items on the table, Diane said, “Did you sit on the benches with many girls?”

“”I was too shy,” said Guillermo. “I was always the second, the sidekick, just being quiet and smiling.”

“He lost that shyness by the time we met,” said Ramona.

to be continued…